Life-force

The Vital Plane of Consciousness — Insights from Integral Yoga

The vital plane impinges on the physical, innervates and energises it to produce the animate world. On the one hand, this impingement produces variety and beauty in the physical forms, on the other, the friction resulting from this impingement results in the first pain whose memory is still carried in our subconscious. But first let us study beauty in its pristine purity.

Pursuit of Beauty

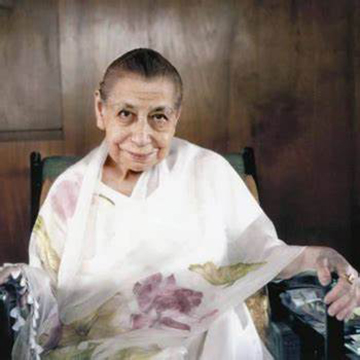

The sense of beauty is not only pleasant for the eyes, it has also a healing touch and is a powerful motivator for inner growth. The vital also carries the turbulence of the passions and can adulterate and vulgarise beauty. The physical has no such problem and can manifest beauty in its pristine purity. It might be argued that everyone cannot cultivate beauty as that needs an aptitude but the Mother explained that the basic programme for a discipline of beauty to be cultivated should be, “…. to build a body that is beautiful in form, harmonious in posture, supple and agile in its movements, powerful in its activities and robust in its health and organic functioning (1).”

One interesting fact is that material needs decrease with spiritual growth and hence there might be a loss of interest in aesthetics and a pursuit of beauty may seem to be an unnecessary exercise. The Mother pointed out that a rejection of aesthetic needs is a regression to a primitive life that is not necessarily right and does not help in the growth and efflorescence of a many-sided, variegated consciousness. The loss in material interests is not a sine qua non of spirituality. It happens not because one has an ascetic pull, but because, “.... the focus of attention and concentration of the being moves to a different domain (2).”

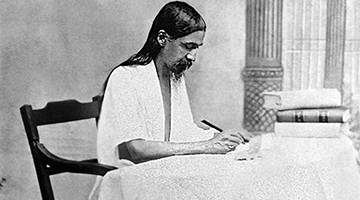

In fact, a refined and sensitive consciousness at a certain degree of development could spontaneously and naturally select its own parameter of beauty that would enhance the pursuit of a divine life. It is wrong to believe that aesthetics serves only our passions and sensations. Beauty is an attribute of the Supreme and aesthetics can be pursued as a gateway to the Divine. As Sri Aurobindo puts it: “Cultivation of the sense of beauty refines the temperament. A refined temperament is much more easy to purify than an unrefined one…. the development of the sense of beauty is as much a part of perfection as anything else. Not only that; if a man has not developed the sense of beauty he would miss the path of approach to the Supreme which is through beauty (3).” Indeed, the Mother considered that the loss of the sense of beauty could become more responsible for the downfall of a nation than poverty.

The Realm of Creativity

Refinement of sensations and cultivation of beauty lead to the realm of creativity. The true realm of creativity is situated at the summit of human consciousness, “on the borderline between what Sri Aurobindo calls the lower and higher hemispheres (4).” It is a world of creation with several zones which the Mother described exhaustively. The first zone is the one of forms that are expressed as paintings, sculptures and architectures. The second is the musical zone with great waves of soundless music that exist per se, without striking any surface and inspire great composers. The third zone is the one of thoughts, organised thoughts for plays and books, abstractions for philosophies. The fourth zone is one of forces that appear as coloured lights without forms. These forces can be combined for terrestrial action. It is a zone of action independent of form, sound and thought and can be used for particular events (5).

“Thus, we have form, expressed in painting, sculpture or architecture; sound, expressed in musical themes; and thought, expressed in books, plays, novels, or even in philosophical and other kinds of intellectual theories (that’s where you can send out ideas that will affect the whole world, because they influence receptive brains in any land, and are expressed by corresponding thoughts in the appropriate language). And above this zone, free of form, sound and thought, is the play of forces appearing as coloured lights. And when you go there and have the power, you can combine those forces so that they eventually materialize as creations on earth (it takes some time, it’s rarely immediate) (6).”

Exploring the Vital

The exploration of the physical is followed by the very difficult task of dealing with the vital plane of consciousness that is the repertoire of our conflicting emotions, turbulent passions and effective dynamisms. One has to cultivate the art of detaching from the outer vital and identify with the inner vital that has the strength of quietude and the peace of silence. A prolongation of such detachment brings one in contact with the Master-Emotion or Bliss behind all emotional dualities and polarities; this Bliss or Ānanda is spontaneously self-existing and does not require any extrinsic motivation and exists de novo for its own inherent joy to be.

The energy available at the outer vital is not inexhaustible, it is clipped down by the inertia and resistance of the physical plane and by doubts, preferential biases and idiosyncrasies at the mental plane. The energy at the inner vital is free from such external constraints and is in turn linked up with the inexhaustible cosmic energy. An access to the inner vital energy can be used for inner growth as well as to support outward activities and can also be used for healing oneself and others. The inner vital reveals that power is not only an outer force but can spring, albeit more powerfully from the poise of silence and peace. It is a common experience that the pursuit and acquisition of power brings disharmony in the being and this may even precipitate stress-linked illnesses. However, power springing from an inner poise of peace and silence does not disrupt the outer harmony and does not usually make one succumb to illnesses.

One of the chief ways to deal with the outer vital is to detach oneself from one’s desires. The Buddha declared that if the satiation of desire gave happiness, the control of desire would be more powerful and give greater satisfaction and joy. Desire itself has a multi-levelled construction and is often camouflaged in befooling garbs like charity, sermons and social service; often sublimated for ego-satisfaction; often pursued for strength and dominance; often rationalised to cover up lapses; often eulogised in the name of basic instincts. It is true that without a modicum of desire, it is difficult to be successful in the material world as it is today. It is also true that massive provocations orchestrated by the global market and cultural consumerism make us succumb rather willingly. As one traverses the inner ranges of the being, the force of desire gets transformed into the will for progress. Among other things, the conquest of desire also needs not to needlessly compete with time. The competition with time is a fallacy of the modern age and gives an illusion of activity; the poise of timelessness helps us to confront the demands of time in the right spirit. The conquest of the vital is of course as difficult an endeavour as like conquering a mountain-top.

Attitude to Wealth

It is interesting that while on one hand, the culture of globalisation that has primarily been initiated by Western thought, revolves around money, academic psychology still studies the main currents of psychology in terms of libido, power, aggression, behaviour, transactions but not directly in terms of wealth. Money comes in secondarily to substantiate psychological attributes like ambition. In the Indian tradition, classical asceticism shunned wealth but a practical approach considered the pursuit of wealth (artha) as important a motivator of life as the pursuit of the Dharma (righteous self-journey), libido (kāma), and the pursuit of liberation (mokṣa). Sri Aurobindo presented a lucid appraisal of the money-power that is neither linked to ascetic rejection or wishful over-indulgence. Money-power is a vital power that needs to be rightly used in the pursuit of personal growth and to serve the Truth.

The first postulate about wealth is that it is not meant for an individual possession, for rationally it belongs to the earth as a whole and metaphysically it belongs to the Divine. It is logical to appreciate that with an ever-growing population, money needs to be distributed in an equitable manner and cannot be allowed to be possessed by a handful. That is why the Mother categorically explained that inheritance would cease one day. “Money does not belong to anybody. Money is a collective possession which should be used only by those who have an integral, comprehensive and universal vision (7).” The Mother added, “Money is a force and should not be an individual possession, no more than air, water or fire. To begin with, the abolishment of inheritance (8).”

The second postulate is based on the fact that the Divine Consciousness is always contradicted by the forces of the Inconscience and hence it is inevitable that the greatest resistance to the right use of wealth arises from the Inconscience. Indeed, at the present time, the true essence of wealth is held ransom by the inconscient forces and needs to be won back for its true worth. Money, “…. is in the clutch of the hostile forces and is one of the principal means by which they keep their grip upon the earth. The hold of the hostile forces upon money-power is powerfully, completely and thoroughly organised and to extract anything out of this compact organisation is a most difficult task (9).” These hostile forces would rather utilise the money to be spent on vital desires like libidinal satisfaction, fame, power and greed for food than to serve the Truth. “To win money from their hands for the Divine means to fight the devil out of them; you have first to conquer or convert the vital being whom they serve, and it is not an easy task (10).”

The third postulate is that the power of money depends on its circulation to serve the Truth and not merely commercial interests and certainly not on its hoarding and the tendency to preserve wealth must be balanced by the tendency to distribute justifiably and for the service of the Higher Consciousness. “This idea that money must make money is a falsehood and a perversion. Money is meant to increase the wealth, the prosperity and the productiveness of a group, a country or, better, of the whole earth. Money is a means, a force, a power, and not an end in itself. And like all forces and all powers, it is by movement and circulation that it grows and increases its power, not by accumulation and stagnation (11).”

These basic postulates recommend that in a pursuit of personal growth, one must neither have an ascetic rejection nor a vital attachment to the money-power but regard it as something that is to be won over for service to the Higher Consciousness….

“If you are free from the money-taint but without any ascetic withdrawal, you will have a greater power to command the money for the divine work…. The ideal Sadhaka (spiritual aspirant) in this kind is one who if required to live poorly can so live and no sense of want will affect him or interfere with the full inner play of the divine consciousness, and if he is required to live richly, can so live and never for a moment fall into desire or attachment to his wealth or to the things that he uses or servitude to self-indulgence or a weak bondage to the habits that the possession of riches create… In the supramental creation the money-force has to be restored to the Divine Power and used for a true and beautiful and harmonious equipment and ordering of a new divinized vital and physical existence…. But first it must be conquered back…. and those will be strongest for the conquest who are in this part of their nature strong and large and free from ego and surrendered without any claim or withholding or hesitation , pure and powerful channels for the Supreme Puissance (12).”

Virtues and Perfection

The value of virtues in personal growth raises an interesting question if one views it not morally but from a wider psychological perspective. Inevitably, personal growth in spiritual terms is apt to be viewed in moralistic terms. However, if a spiritual perspective of growth is not strictly restricted to the religious paradigm but is based on ever-expanding vistas of consciousness, then a life tied down to virtues would not fully reflect the truth of existence. The Consciousness that preceded creation had no divisions and so was simple but once creation was permitted, Consciousness had to become complex and manifold and now if the original simplicity has to be experienced, it has to be done in a new denouement, with a manifold and rich simplicity. “Nature in its effort towards expression, was compelled to have recourse to an unbelievable, almost endless complexity in order to reproduce the original Simplicity. It brings us back to the same thing: it is that excess of complexity which makes possible a simplicity that isn’t empty — a rich simplicity. An all-embracing simplicity, whereas without those complexities, simplicity is empty (13).” Naturally, as a corollary, life itself becomes complex and it would be oversimplified to tie it to a set of virtues. That does not mean we have to shun virtues for an immoral life; rather virtues have to be placed in their proper context in the holarchy of consciousness along with other elements needed for growth and perfection.

The Mother explained:

“Virtue claims to seek perfection, but perfection is a totality. So the two movements are contradictory: virtue, which eliminates, prunes, sets limits, and perfection, which accepts everything, rejects nothing but puts everything in its place, evidently cannot go well together.

“Taking life seriously generally consists of two movements: the first is to give importance to things that probably have none, and the second is to want life to be limited to a certain number of qualities considered to be pure and worthy. With some, that virtue becomes dry, barren, grey, aggressive, and almost always finds fault in all that is joyful, free and happy.

“The only way to make life perfect is to look at it from a sufficient height to see it in its totality, not only its present totality, but over the whole past, present and future: what it has been, what it is, what it must be — you must be able to see it all at once. Nothing can be done away with, nothing should be done away with, but each thing must find its own place in total harmony with the rest. Then all those things that appear so ’evil’, so ’reprehensible’ and ’unacceptable’ to the puritan mind would become movements of joy and freedom in a totally divine life. And then nothing would stop us from knowing, understanding, feeling and living this wonderful Laughter of the Supreme who takes infinite delight in watching Himself live infinitely.

‘This delight, this wonderful Laughter which dissolves all shadows, all pain, all suffering…We only have to go deep enough into ourselves to find the inner Sun and let ourselves be bathed in it. Then everything is but a cascade of harmonious, luminous, sun-filled laughter which leaves no room for shadow and pain.

“In fact, the greatest difficulty, even the greatest grief, even the greatest physical pain, if you can look at them from there, you see the unreality of the difficulty, the unreality of the grief, the unreality of pain — and all becomes a joyful and luminous vibration (14).”

References

1. The Mother. The Collected Works of the Mother, Volume 12. 2nd ed. Pondicherry: Sri Aurobindo Ashram Trust; 1999, p. 50.

2. The Mother. Mother’s Agenda, Volume 11. Paris: Institut de Recherches Evolutives; 1981, [English transl.] p. 117.

3. (Recorded by) Purani AB. Evening Talks with Sri Aurobindo. 2nd Impression. Pondicherry: Sri Aurobindo Ashram Trust; 1995, p. 455.

4. The Mother. Mother’s Agenda, Volume 3; 1979, p. 387.

5. Ibid., pp 389.

6. Ibid., pp. 389-90.

7. The Mother. Collected Works, Volume 13; 2003, p. 271.

8. The Mother. Mother’s Agenda, Volume 1; 1978, p. 206.

9. Mother. Collected Works, Volume 3; 2003, p. 45.

10. Ibid., p. 46.

11. The Mother. Collected Works, Volume 13, p. 149.

12. Sri Aurobindo. The Complete Works of Sri Aurobindo, Volume 32. Pondicherry: Sri Aurobindo Ashram Trust; 2012, p. 11.

13. The Mother. Mother’s Agenda, Volume 4; 1979, p. 142.

14. Ibid., p. 30.

Share with us (Comments, contributions, opinions)

When reproducing this feature, please credit NAMAH, and give the byline. Please send us cuttings.