Music therapy

Musical Notes and Emotions

Abstract

The article analyses the formal and therapeutic aspects of the musical scales used in the practice of Nāda Yoga as a fundamental means to transform emotional energy blocks which, on a psychosomatic basis, are considered one of the main causes of physical, physiological and psychological problems. On the base of the monodic modal, the musical system used in Indian classical music, it is possible to assign a precise emotional value to each of the notes that make up an octave. This makes it possible to safely and objectively apply the singing practice of sound patterns to any subject, regardless of nationality, culture and personal experiences. Two cases are reported with details of this therapeutic practice.

Let’s consider the aspect of the emotional connection, which is very important and fundamental in the practice of therapeutic musical scales and in the rāga therapy system. In the Indian musical system, the modal-monodic principle is followed, in which the use of harmony, the so-called vertical musical structure, given by the addition of at least three different pitches (chord), is absolutely not taken into consideration. This method allows you to clearly and unambiguously assign a precise emotional value to the various intervals obtained by relating the different pitches (notes) to an immutable base, called tonic or drone. This mechanism allows you to know in advance what the emotional response of anyone who listens (or sings) these sound reports will be, regardless of nationality, culture, age, gender or personal history. This is because a mechanism relating to the so-called ‘unconditioned mind’ comes into action: there are sounds that do not pass through the intellect and do not have to be stored in the mind to be identified, but have an immediate reflection on their understanding without conditioning the mind. They are very primitive sounds and are the pure reflection of emotions. Among these, the musical intervals (notes)1, the harmonisation, which from an aesthetic-intellectual point of view is a very interesting and valid operation and can give many more nuances, but from the point of view of the clarity and objectivity of the emotions aroused, complicates things and does not make it possible for a generalised and safe application of music on a therapeutic level, bringing into play personal factors linked to individual experiences. The monodic modal system, more elementary and primitive (in a good sense), instead allows a safe cataloguing process of the various musical intervals (notes). In fact, it is the interval that allows you to arouse and evoke a psychic-emotional state, and not the name of the note, which depends on the tonality chosen.

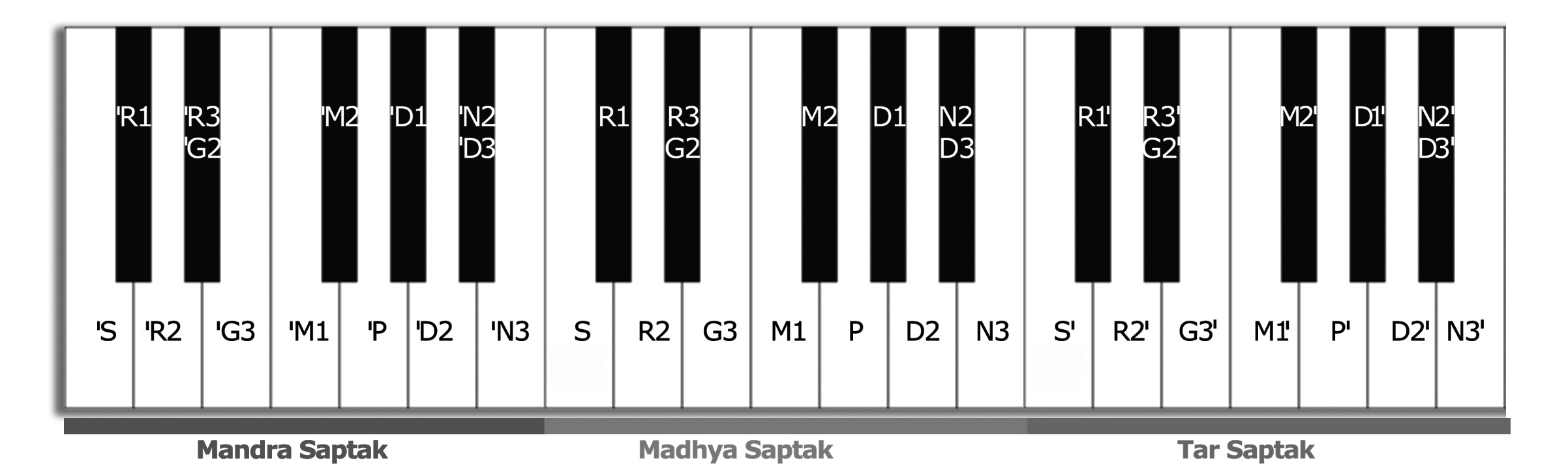

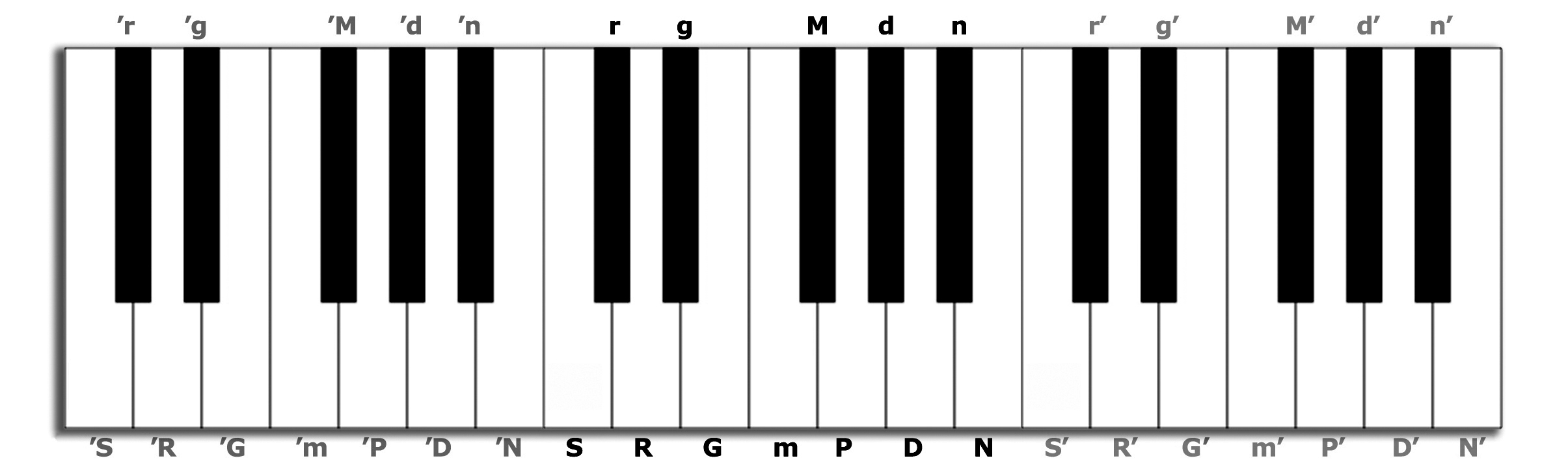

Based on this principle, we are going to list the possible emotions related to the intervals. For this purpose we shall use the interval nomenclature system used in Nāda Yoga, which is a simplification of the one in force in the Carnatic musical system of south India. In the following table you can see the sequence and denomination of the intervals in the different systems.

Fig.1: South India (Carnatic) notation system, in three octaves (saptaka): bass (mandra), middle (madhya) and high (tar)

Fig.2: North India (Hindustani) notation system

Fig. 3: Simplified Nāda Yoga system and correspondence of the notes in English notation

The following table shows the main emotional states that arise from the relationship of each single interval with the fundamental. To simplify, we consider a fundamental in Do (Sā), bearing in mind that this can be chosen from among the 12 possible options, without anything changing regarding the emotional value that arises.

Sā (C) on Sā (C): does not give an emotion, as there is no relationship, being the same note

Re1 (Db) on Sā: here an emotion is born that we can define as anxiety, discomfort, fear, ferment, tension (sometimes even positive, in the sense of ‘awakening’)

Re2 (D) on Sā: positive, expected, comfortable

Gā1 (Eb) on Sā: sentimental, melancholy, light sadness

Gā2 (E) on Sā: strength, positivity, security

Mā1 (F) on Sā: compassion

Mā2 (F#) on Sā: loving, sadness, sentimental affection

Pā (G) on Sā: happiness, well-being, harmony, loving kindness

Dhā1 (Ab) on Sā: worry, anxiety, sadness, distrust

Dhā2 (A) on Sā: joy, strength, courage, confidence

Nī1 (Bb) on Sā: delicacy, attraction, sensuality

Nī2 (B) on Sā: evaluation, intellectuality, challenge, anger, resolution, tension

It is also important to underline that in a melodic sequence (in our case a scale), each interval is influenced by the one that precedes and in turn influences the one that follows, thus enhancing or blurring the basic emotional character, a character that can have various interpretative nuances, but which is always very clear and defined in its basic essential value. This allows you to use the scales in a safe and objective way, i.e. with equal answers on any subject.

Thus the use of therapeutic musical scales is being outlined with ever greater precision, understood as mathematical formulas of intervals which are based fundamentally on a basic sound/note (tonic or drone). The result is a melodic path (horizontal structure) which singing (or even simply listening to) produces a succession of different emotional states. The therapeutic principle provides that the various emerging tensions are gradually transformed into a final positive emotion, where the so-called conversion of negative emotional energies, or emotional energy blocks, will have taken place, considered the primary cause of many pathologies (psychosomatic principle). For some scales, then, it is possible to consider the physical vibratory action in specific points/zones/organs of the body, for a function of restoring the energy levels in disequilibrium. This is because it should be kept in mind that the singing of the scale always produces a double level of action: one in the physical body and the other in the psychic and emotional sphere.

The Practice of Singing Therapeutic Musical Scales

We now come to consider the practice of singing according to the principles and techniques of Nāda Yoga. This discipline (because this is what it is about) is very ancient and we can also find traces of it in the Greek world. Pythagoras, in fact, made his disciples sing the scales (modes), even if only in the descending phase, i.e. skipping the ascending one. The reason lies in the fact that, as we will see, the ascending phase is responsible for the transformation of emotional energy-blocks, while in the descending phase a consolidation of the result and a form of psychic and spiritual enrichment, of evolutionary growth takes place. Pythagoras’ pupils had already largely passed the first phase and the higher level was destined for them.

By ‘scale’ we mean a sequence of intervals (they can be of seven, six or five notes) which, starting from a tonic of your choice, arrive at the same note, but at the octave (and therefore double the initial frequency). This is technically ‘one way’. In the musical system of south India (Carnatic) we have 72 basic heptatonic scales (with seven different notes) — Melakartā System, from which other scales with six (hexatonal) or five notes (pentatonic) can be obtained. The scales are grouped in two sectors, the first of which always has the Mā1 (Śudda Madyama) present, the second (Prathi Madyama) always the Mā2.

The Melakartā System was proposed by Rāmamātya in his work Svaramelakalānidhi (c. 1550). He is considered the father of the mela system of rāgas. Later, Venkatamakhi in the 17th Century, exhibited his work, Caturdandi Prakāssikā, a new cataloguing known today as Melakartā.

The therapeutic scales are toned using the pronunciation of the phonemes corresponding to the Carnatic system, both in the ascending phase (Sā, Re, Gā, Mā, Pā, Dhā, Nī, Sā), and in the descending phase (Sā, Nī, Dhā, Pā, Mā, Gā, Re, Sā), with a rhythmic division which, starting from a value of 4/4 per note, continues by gradually halving the speed, until reaching the maximum possibility. As a starting tonic note, it would be advisable to use the one corresponding to your own personal Tonic2 or, not knowing it, choosing between G and C, the most suitable ones for generic use. As a basic rhythm, the speed should be that of your natural rhythm: to find it, just do a few pulse checks as soon as you wake up in the morning in a natural and relaxed way, then possibly making an average if there are different readings. That value corresponds to our natural rhythm, called rest. On that frequency (and multiples and submultiples) we can start on any physical activity (walking, talking, playing, dancing, etc.) with maximum performance and minimum energy consumption. Furthermore, by setting it to a metronome and letting it go in the background while we do other things, the pulsations will tend to bring our heartbeat a little at a time to that optimal value (it is the same mechanism that the shaman uses with the drum to bring back to the right rhythm the heartbeat altered by an illness).

As a practical example, we report some cases of users/patients to whom specific therapeutic techniques have been applied, with the use of musical scales obtained from the Melakartā System.

Case Study No.1

The subject in question was a woman of around 37-years-old (Anna C.), in good general health, but with a recent problem regarding the blockage of menstruation, a phenomenon which had been repeating for a couple of months, also causing the subject a related state of anxiety and slight depression.

The first procedure consisted of detecting her personal tonic note.3 This examination of her voice, lasting approximately an hour, allows us to determine what is considered the basic frequency corresponding to the state of centredness, psycho-physical efficiency and emotional balance. This frequency corresponds to one of the 12 notes into which the octave is divided in the temperate system used in the West. Its physical location is at the navel. All the techniques foreseen by Nāda Yoga will be based on this note, starting from the practice of the OM Mantra (AUM) which, in the structuring foreseen by Professor Shri Vemu Mukunda, is divided into the intonation of the three separate phonemes A, U, M to be done with a simple Prānnāyāma formula which includes times of inhalation (Puraka), retention (Kuṃbaka) and exhalation (Recaka) accompanied by free singing. The use of the personal tonic note ensures greater precision of the vibratory energy both from a physical and psychic-emotional point of view but even not knowing it you can still work well with C or G.

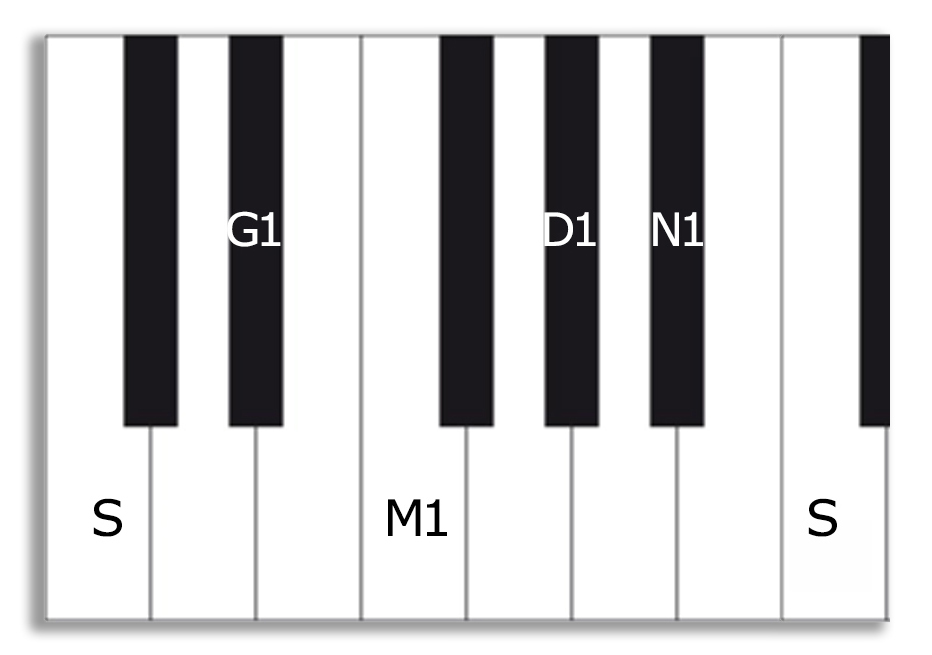

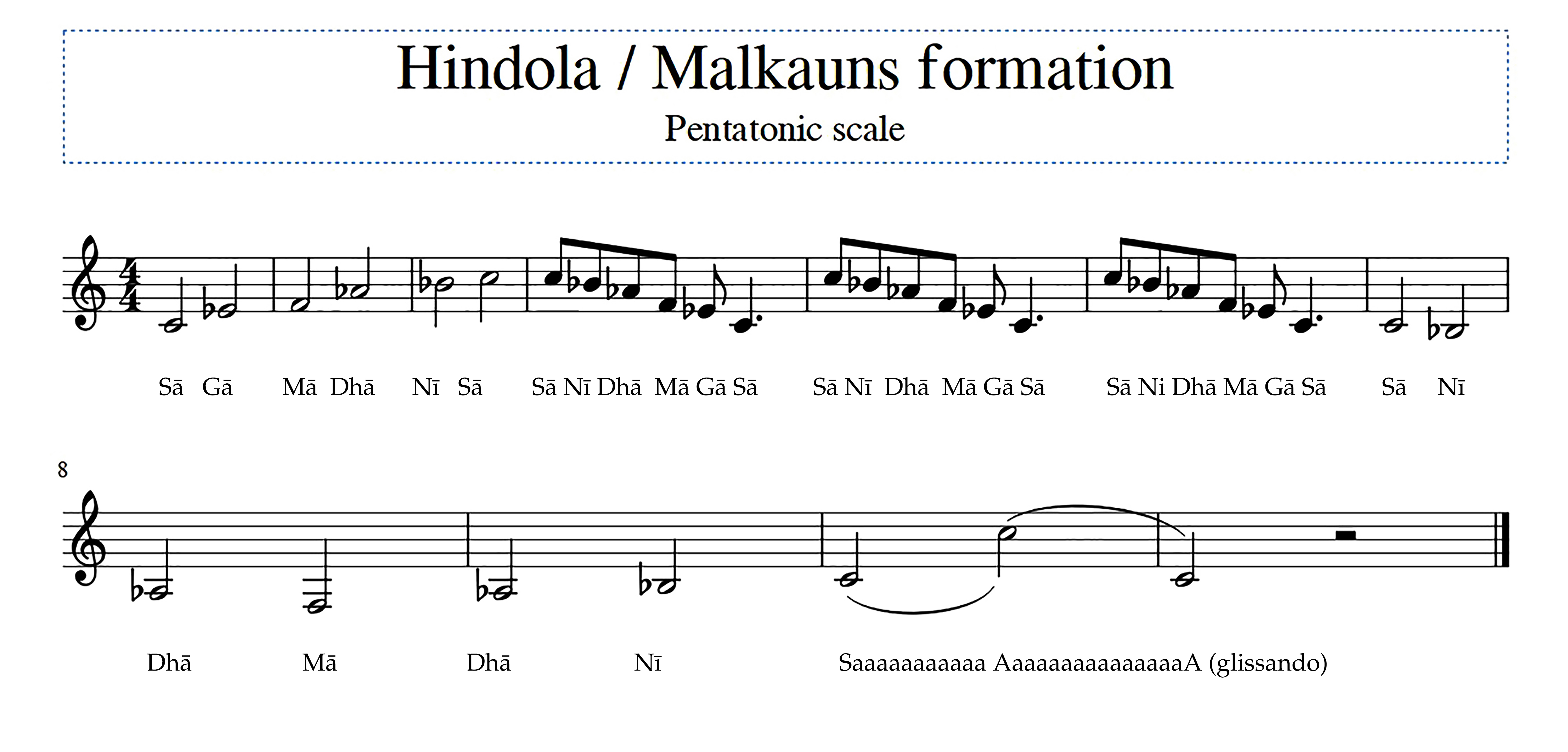

This procedure is accompanied by concentration in the three psychophysical points (Granthī)4 of the navel (A) to stabilise the centring, of the heart (U) to bring out the so-called ‘absolute joy’ (Ānanda) and of the third-eye (M) to increase the mental abilities of attention, concentration, memorisation and development of intuition. The second phase consists in the use of the actual Mantra5, intoning a long glissando starting from A on the tonic note and then arriving and concluding, passing on the U sound, to the M sound at the octave: this modality is considered the true original form of using the OM Mantra to obtain the precise result of the transformation of emotional energy-blocks and the recovery of new energy to be used for self-therapy and creativity, and also restoring the correct functioning of the organism on a physiological, psychic and emotional level. The glissando is a particular gamaka (embellishment) with which all the frequencies included in an octave are touched, well beyond the 22 codified microtones (śrutis) of Indian music. Afterwards, the subject was prescribed the practice of singing a specific therapeutic musical scale, based on the Hindola/Malkauns pentatonic scale.

Fig. 4: Western Musical notation of Hindola/Malkauns scale

Fig. 5a): Hindola/Malkauns scale in Melakartā System

b) in Nāda Yoga simplification

| C | E♭ | F | A♭ | B♭ | C | ||

| SA | GA | MA | DHA | NI | SA | ||

| 1 ½ | 1 | 1 ½ | 1 | 1 |

Fig. 6: Hindola/Malkauns with English notation and tones intervals

From the analysis of the intervals, we can immediately notice the ‘feminine’ character of all four notes (with the exception of the tonic which is neutral), which is significant for the application on female subjects: the vibratory energy of the phonemes will therefore go to work emotionally in a way centred on the psychic structure of the woman.

The first step in the procedure consisted in training the subject to correctly pronounce the phonemes of the scale, both in the ascending and descending phases; then in the sequence with the metric division of four beats per note, then two beats, one and finally half. This formula allows the Prāṇa6 to be conveyed fully and effectively, thanks to the metric structure used which also involves breathing.

In addition to establishing the personal tonic note, in the first session, the subject was trained to find her own natural rhythm. It is the heart rate that corresponds to the so-called resting rhythm, on the basis of which any activity can be done (walking, talking, writing, playing, etc.) with the lowest energy consumption and maximum efficiency. This applies both to the basic rhythm and to multiples and submultiples, which means that we can do things both quickly and slowly, it doesn’t matter, the important thing is that we act on the basis of the natural rhythm. To find it, the subject was invited to detect the heartbeat at the moment of natural awakening, make a few movements in bed, which is needed to take the watch and test the pulse to check how many beats there are per minute. This procedure will be followed for other measurements in the following days (if there are differences, an average will be taken). The frequency detected will correspond to your natural rhythm and on that basis the inhalation and retention times will be calculated, which must be the same.

The singing in the exhalation is free, as long as there is breath. After this first phase, a particular ‘training’ was applied, which consists in repeating the descending phase of the scale three times with only the phoneme ‘A’, and then to descend in the low octave up to Mā, go back up to Sā and then implement an ascending glissando up to the high octave Sā and then ending with a descending glissando up to the tonic Sā. If there are difficulties in tuning the notes in the lower octave, mental chanting (anāhata) will be used. The patient was advised to practice this procedure daily, with particular attention to the period in which menstruation would normally have occurred. Within two months of continuous practice, menstruation reappeared regularly, restoring the woman to full physical and emotional efficiency.

Fig. 7: Hindola Malkauns formation

Case Study No. 2

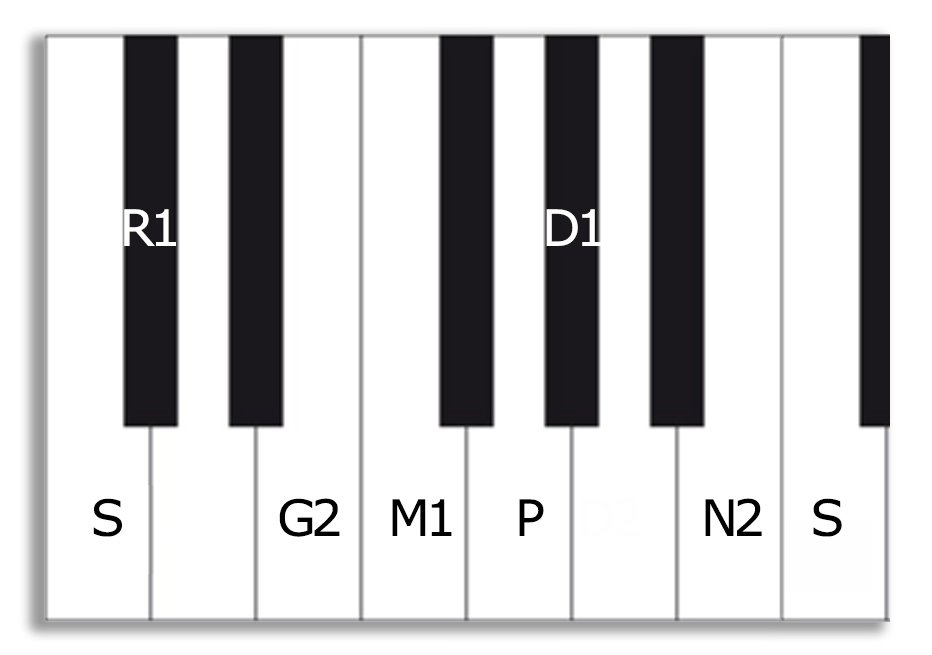

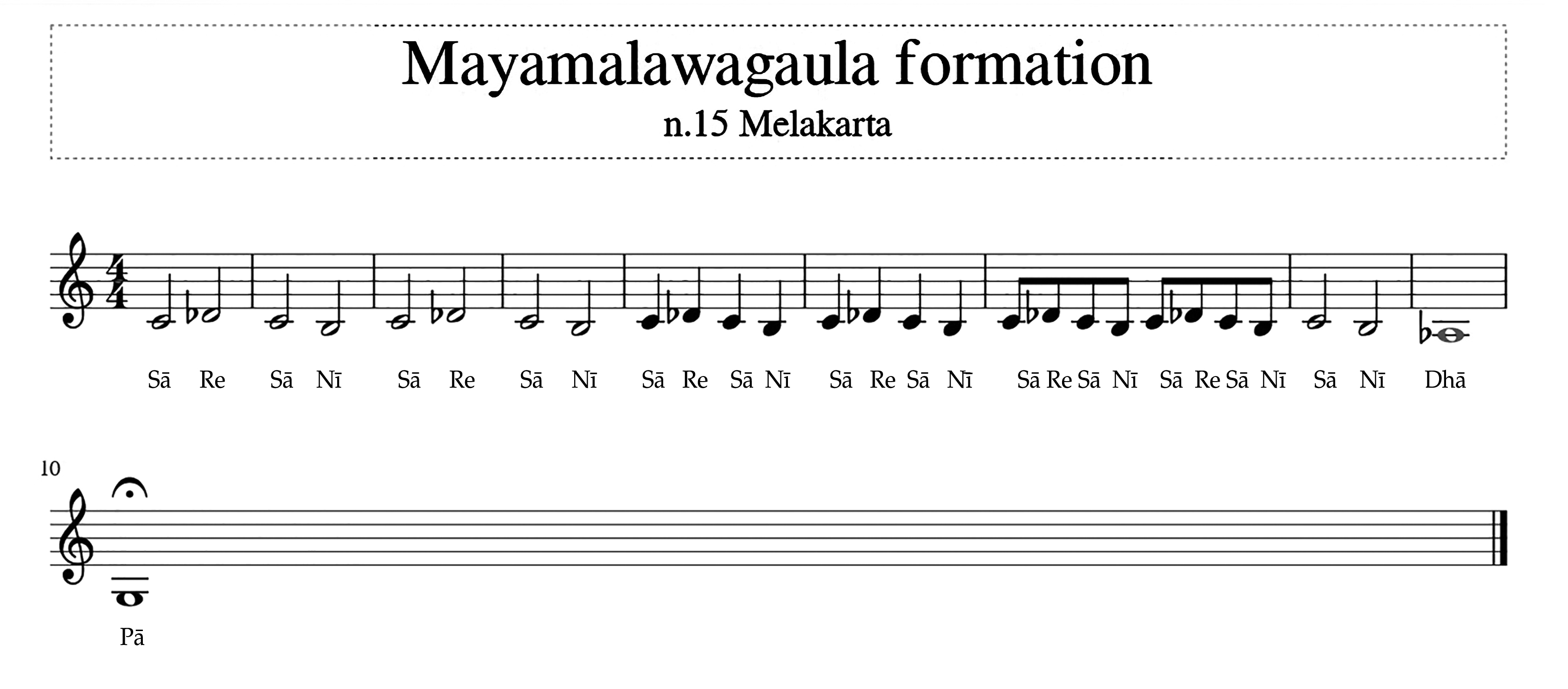

In this second case, referring to a 40-year-old man (Carlo M.), suffering from constipation, the chanting of the Mayamalawagaula scale (n. 15 Melakartā) was applied after the usual initial practice of the AUM Mantra. This heptatonic scale is one of the four fundamental scales in Nāda Yoga, together with the n.22 Karaharapriya, the n.29 Diraśankarabaranam and the 65 Mlechakaliyāṇi. Mayamalawagaula is also the reference scale in the Carnatic musical practice of south India (in the northern Hindustani system it is based instead on the Kalyan That (Mlechakaliyāṇi).

In the Nāda Yoga discipline, this scale is used for various purposes, the first of which is to act on attention, concentration, memorisation and coordination of the cerebral hemispheres, in practice on what we can define as ‘operational intelligence’. In schools in South India, students are made to sing at the beginning of lessons, in order to awaken their attention and prepare them for learning.

Fig. 8: Western Musical notation of Maya-malawagaula scale

Fig. 9 a): Mayamalawagaula scale in Melakartā System and

b) in Nāda Yoga simplification

| C | D♭ | E | F | G | A♭ | B | C |

| SA | RE | GA | MA | PA | DHA | NI | SA |

| ½ | 1½ | ½ | 1 | ½ | 1 ½ | ½ |

Fig. 10: Mayamalawagaula with English notation and tone intervals

It is a particular scale that has two important structural characteristics. It is coherent, that is, it has the same intervals in both the ascending and descending phases, and then it is symmetrical: the intervals of the first section (Sā-Mā) are the same as those of the second (Pā-Sā). In addition, it contains two long intervals of one and a half steps (R - G and D - N). These characteristics contribute to acting positively on brain synapses, taking into account that when a given musical formula is sung, the brain makes a series of calculations and proportions that strengthen neuronal connections, contributing to greater mental brilliance and elasticity [1].

In the specific case in question, to resolve the problem of constipation, the scale is made to tune with a particular formation which involves the use of the low octave, first with the rhythmic repetition, at increasing speed, of the formula Sā Re Sā Nī (low octave) and then the descent from the tonic Sā, Nī Dhā to the low octave Pā, with which it concludes. Also in this case, if there are difficulties in intoning the notes in the lower octave, mental chanting (anāhata) will be used. The Sā Re1 interval has the property of acting on a physical level in the area above and below the navel and on a psychic-emotional level it generates a slight sensation of excitement, of awakening. Physiologically, there is a stimulation of the colon with gastric juices normally used for digestion, favouring in this case, the evacuation process with the final sequence downwards.

Fig. 11: Mayamalawagaula formation

After assiduous and regular practice, within three weeks there were clear improvements in his digestive capacity and greater regularity in evacuation. The patient also noted a better ability to concentrate and improved mental clarity.

Finally, an important development in the practice of therapeutic musical scales consists in the passive application of sound models, implemented by listening to Rāga (compositions of classical Indian music) based on the scales chosen for the specific problems. Each rāga is based on a precise musical scale and elaborates it according to a pre-established sequence, which includes a long, free introduction, without rhythm (Alāp), in which the typical mood of the composition is introduced by presenting the main notes (Vadi and Samvadi). Afterwards the rāga develops with a theme (Gat) based on a rhythmic cycle (Tāla), interspersed with improvisations, which however respect the fixed scale and the rhythmic cycle, with a crescendo in speed until reaching the very fast finale (Jhala). Listening to a Rāga (which must have a significant duration, at least 15/30 minutes) allows the subject to move emotional energies in a significant way, with effects of transforming energy-blocks similar to what is obtained with singing. This procedure is now consolidated in some hospitals in India, with detailed protocols that allow feedback on patient samples, and the results are appreciable and verifiable [2].

As an example, we propose the 20th Melakartā: Naṭa Bhairavī (corresponding to the natural minor aeolian mode), on which the Rāga Darbāri Kānada is based, and which has been widely used with excellent results in the treatment of problems such as insomnia, depression and anxiety and as an anti-stress during post-surgical discomfort [3].

Fig. 12: Nata Bhairavī (aeolian mode) notation — Rāga Darbāri Kānada

Conclusion

From the analysis of the structural and functional characteristics of therapeutic musical scales, it can be concluded that we are witnessing the emergence of a great healing potential capable of transforming emotional energy-blocks in subjects who sing the appropriate scales, following the indications of the procedure, with continuity and regularity. The practice does not require long application times, just regular daily execution lasting about 10 minutes is sufficient. This technique, along with many others (that are part of the Nāda Yoga system) is based on the ancient practices of the Indian musical tradition and has always been used for psychophysical well-being.

References

1. Wan CY, Schlaug G. [Online] Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2996135/ [Accessed 22nd March 2024]. Music Making as a Tool for Promoting Brain Plasticity across the Lifespan. Neuroscientist 2010; 16: 566-77.

2. Vaishnav S, Chowdhury AB, Raithatha N, Panchal N, Prabhakaran A, Kalaskar P, et al. [Online] Available from: https://www.ijoyppp.org/article.asp?issn=2347-5633;year=2021;volume =9;issue=2;spage=73;epage=79;aulast=Vaishnav; type=0 [Accessed 22nd March 2024]. Receptive Music Therapy: An Effective Means to Enhance Well-being in Patients undergoing Caesarean Section and Hysterectomy and Their Operating Team. Int. J Yoga - Philosop Psychol Parapsychol 2021; 9(2):73-79.

3. Mukherjee SC, Mukherjee R (Visva Bharati University). [Online] Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2996135/ [Accessed 22nd March 2024].Role of Music Therapy Intervention Using Raga Darbari Kanada of Indian Classical Music in the Management of Depression, Anxiety, Stress, and Insomnia. Research Review International Journal of Multidisciplinary May 2019; 4.

Bibliography

Mukherjee P. The Scales of Indian Music. New Delhi: Aryan Books International; 2004.

Daniélou A. Introduction to the Study of Musical Scales. New Delhi: Oriental Books Reprint Corporation; 1979.

Misto R. Therapeutic Musical Scales: Theory and Practice.OBM Integrative and Complementary Medicine 24th May 2021; 6 (2).

1 Cfr. Shri Vemu Mukunda

2 The personal tonic note is the frequency (expressed in Hertz) detectable in the spoken voice, which corresponds to the state of calm, centeredness and mental lucidity: it is physically located at the navel.

3 In Hindu philosophy, we talk about a sound called Ādhāra Shadja. Ādhāra means base, support, Shadja means tonic. This is talked about in many texts, but no one had understood it well. People who practise Nāda Yoga have tried to find the tone through Svara Shadja Kara, which means realising the note that connects to cosmic energy.

4 Granthī are the important points where the three main channels (nādis) of Prāṇa (Suṣmnā, Iḍā and Piṅgalā) join.

5 Cfr. Praśna Upaniṣad

6 Regarding the type of Prānna in question, Sā and the note with a fifth interval (Pā) stimulate Sāman and restore balance and coordination. The Dhā, Nī and Sā octave intervals stimulate Prānna. Re, Gā Mā and the notes in the lower octave stimulate Apāna. The notes in the upper octave stimulate Udāna and Vyāna.

Dr. Riccardo Misto is Director of Nada Yoga Centre, Padova, Italy.

Share with us (Comments,contributions,opinions)

When reproducing this feature, please credit NAMAH,and give the byline. Please send us cuttings.