Psychology

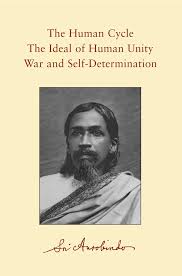

Sri Aurobindo’s Comments on Western Psychology

Abstract

It is interesting to note Sri Aurobindo’s observations on the emerging Western psychology. But the human being is a transitional being and subject to continuous change. Western psychology studies this change in social, cultural, environmental, genetic and technological terms. In Sri Aurobindo’s cosmology, this change is an evolutionary one in consciousness, as the individual traverses supra-rational cognitive matrices, heralding the emergence of a consciousness based psychology.

Sri Aurobindo did not write a textbook of psychology but his writings are full of seed-ideas that can be extrapolated to build a comprehensive approach to psychology. His main writings, which later on appeared as books, were simultaneously written during the turbulent times of World War I and its aftermath. These writings, which are full of psychological insights, started to be serialised in the journal, Arya from 1914 onwards. It seems that Sri Aurobindo was well aware of the main currents of thought prevalent in Western psychology before he started writing his magnum opus, The Life Divine. In numerous drafts, letters and writings, he had been commenting on aspects of Western psychology since 1912-13. Much like a seasoned researcher, he made an overview of the contemporary movements in psychology before he embarked on presenting his own experiential constructs. Some of his comments on various issues are listed not merely for historical interest but to demonstrate how his ideas for a futuristic psychology started to build up momentum.

Comments on early psychological thinking in the West

He had observed how the old structuralistic, functionalistic and Pavlovian ways of thinking were being supplemented by the emerging psychoanalytic trends. In 1912-13, he wrote:

”Exact observation and untrammelled, yet scrupulous experiment are the method of every true Science. Not mere observation by itself —for without experiment, without analysis and new-combination observation leads to a limited and erroneous knowledge; often it generates an empirical classification which does not in the least deserve the name of science. The old European system of psychology was just such a pseudo-scientific system. Its observations were superficial, its terms and classification arbitrary, its aim and spirit abstract, empty and scholastic. In modern times a different system and method are being founded; but the vices of the old system persist. The observations made have been incoherent, partial or morbid and abnormal; the generalisations are for too wide for their meagre substratum of observed data; the abstract and scholastic use of psychological terms and the old metaphysical ideas of psychological processes still bandage the eyes of the infant knowledge, mar its truth and hamper its progress. These old errors are strangely entwined with a new fallacy which threatens to vitiate the whole enquiry, — the fallacy of the materialistic prepossession (1).”

“But observation without experiment leads only to a limited and erroneous science, often to an empirical system of surface rules which do not deserve the name of science at all. It is this defect which has so long kept European psychology in the status of a pseudo-science; and, even now when real observation has begun and experimentation of an elementary kind is being attempted, the vices of the perishing socialism mar and hamper this infant knowledge (2).”

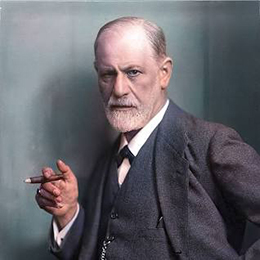

Comments on psychoanalysis

Sri Aurobindo appreciated the emergence of psychoanalysis vis-à-vis the old European systems of psychology but cautioned about the crudities of the new method. In 1915, he wrote:

”It is true that psychology has made an advance and has begun to improve its method. Formerly, it was crude, scholastic and superficial systematisation of man’s ignorance of himself. The surface psychological functionings — will, mind, senses, reason, conscience, etc., — were arranged in a dry and sterile classification; their real nature and relation to each other were not fathomed, nor any use made of them which went beyond the limited action Nature had found sufficient for a very superficial mental and psychic life and for very superficial and ordinary workings. Because we do not know ourselves, therefore we are unable to ameliorate radically our subjective life or develop with mastery, with rapidity, with a sure science the hidden possibilities of our mental capacity and our moral nature.

The new psychology seeks indeed to penetrate behind superficial appearances, but it is encumbered by initial errors which prevent a profounder knowledge — the materialistic error which bases the study of mind upon the study of the body; the sceptical error which prevents any bold and clear-eyed investigation of the hidden profundities of our subjective existence; the error of conservative distrust and recoil, which regards any subjective state or experience that departs from the ordinary operations of our mental and psychical nature as a morbidity or a hallucination — just as the Middle Ages regarded all new science as magic and a diabolical departure from the sane and right limits of human capacity and finally, the error of objectivity which leads the psychologist to study others from outside instead of seeing his true field of knowledge and laboratory of experiment in himself. Psychology is necessarily a subjective science and one must proceed in it from the knowledge of oneself to the knowledge of others’.

“But whatever the crudities of the new science, it has at least taken the first capital step without which there can be no true psychological knowledge; it has made the discovery which is the beginning of self-knowledge and which all must make who deeply study the facts of consciousness, — that our waking and surface existence is only a small part of our being and does not yield to us the root and secret of our character, our mentality or our actions. The sources lie deeper. To discover them, to know the nature, and the processes of the inconscient or subconscient self and, so far as is possible, to possess and utilise them as physical science possesses and utilises the secret of the forces of Nature, ought to be the aim of a scientific psychology (3).”

Sri Aurobindo also commended the psycho-analytic work with dreams, “…. the new method of psycho-analysis, trying to look for the first time into our dreams with some kind of scientific understanding, has established in them a system of meanings, a key to things in us which need to be known and handled by the waking consciousness; this of itself changes the whole character and value of our dream-experience. It begins to look as if there were something real behind it and as if too that something were an element of no mean practical importance (4).”

He, of course, pointed out that there were other sources from which dreams arise, which have not been probed by psychoanalysis. In 1914, Sri Aurobindo also wrote:

“The possibility of a cosmic consciousness in humanity is coming slowly to be admitted in modern Psychology (5).”

A comment which was made at a time when there was an extension in the realm of psychology from the Freudian unconscious to the Jungian collective unconscious. A comment that held the incipient seed-ideas of the transpersonal movement in psychology and which would appear after half a century. Incidentally, Sri Aurobindo was also particular about the `crudities’ of psychoanalytic thinking:

“It (psychoanalysis of Freud) takes up a certain part, ... the lower vital subconscious layer, isolates some of its most morbid phenomena and attributes to it and them an action out of all proportion to its true role in the nature. Modern psychology is an infant science, at once rash, fumbling and crude. As in all infant sciences, the universal habit of the human mind — to take a partial or local truth, generalise it unduly and try to explain a whole field of Nature in its narrow terms — runs riot here….

"I find it difficult to take these psycho-analysts at all seriously when they try to scrutinise spiritual experience by the flicker of their torch-lights…. They look from down up and explain the higher lights by the lower obscurities; but the foundation of these things is above and not below…. The superconscient, not the subconscient, is the true fountain of things. The significance of the lotus is not to be found by analysing the secrets of the mud from which it grows here; its secret is to be found in the heavenly archetype of the lotus that blooms for ever in the Light above (6).”

Inspired by Freud, the Indian Psychoanalytic Society was founded in Calcutta by Girindra Sekhar Bose in 1921 and one of its chief patrons was Owen A.R. Berkeley-Hill, Medical Superintendent of the Ranchi European Mental Hospital. Both Bose and Hill were the pioneers of the psychiatric and psychoanalytic movement in India. Bose started the first ever psychiatric out-patients’ department in any general hospital of India (outside of a mental asylum) at the Carmichael College (now R. G. Kar Medical College & Hospital) in Calcutta in 1933, while Hill was responsible for initiating postgraduate studies in psychiatry for the first time in India. Both Bose and Hill published quite a number of research papers.

There is evidence to suggest that Sri Aurobindo knew something about some of their ideas. It was a time when the word `complex’ was eulogised following the unravelling of the Oedipal complex by Freud. Hill suggested that the Hindu-Muslim communal conflict could be tackled by resolving the `cow-complex’. In a reported conversation on 30.08.1925, Sri Aurobindo had commented on Hill’s view and pointed out that though the phenomenon of repression existed which could be worked through in therapy, a generalisation like resolving the cow-complex for communal harmony would be too far-fetched. When asked how it was that Freud who originated the theory of complexes could have cured people by his theory if it was based on an imperfect foundation, Sri Aurobindo reportedly answered in his characteristically brain-teasing way:

“Theory can never cure anybody. Do you believe that a theory cures? Curing people, or getting a certain result, does not depend upon the theory at all. A theory may be true or false and yet you may obtain results from it. A theory simply puts you in a condition when something behind you can work through you. That is the whole stand of Bergson. Theory merely convinces you and thereby produces the necessary inner condition. That is all. It may be true or it may be false. Freud may have cured people…. But does he cure them by his theory? Not at all; it is because he has some power that people get cured by him (7).”

He elaborated this stance on theorisation in one of his letters while commenting on conflicting theories underlying different therapeutic modalities:

“A theory is only a constructed idea-script which represents an imperfect human observation of a line of process that Nature follows or can follow; another theory is a different idea-script of other processes that also she follows or can follow…. all are only outward means and what really works are unseen forces behind; …. if one can make the process a right channel for the right force, then the process gets its full utility — that is all (8).”

While Hill suggested `social reform’ through psychoanalysis to resolve the Hindu-Muslim conflict, Bose initiated a movement to understand Indian mythology, Indian religion and Indian philosophy through psychoanalysis, a lineage carried on in the 21st century by men like Kakkar. This quest led to a number of attempts to view Krrssnna as a master psychoanalyst who analysed Arjuna and resolved his complexes. Commenting on such ideas which sought to explain anything by psychoanalytic theory, in an informal talk on 4.01.1939, Sri Aurobindo pointed out that there was an inherent contradiction in the psychoanalyst’s position. If the unconscious was really an unconscious (Sri Aurobindo used the term inconscient), how could it throw up repressed things and raise symbols in one’s consciousness. He was hinting that the unconscious could not logically possess `conscious’ activities like propelling up repressed elements to the conscious zone (9)."

Obviously, such a technology if it could at all be applied by the unconscious, then the unconscious could not be truly unconscious! (Sri Aurobindo had by this time already established his realisation that the unconscious or `Inconscience’ was actually a mask of consciousness). He reportedly remarked:

“Modern psychology is only surface deep. Really speaking a new basis is needed for psychology. The only two important requisites for real knowledge of psychology are:

(i) Going inwards, and

(ii) Identification (meaning `experiential knowledge’)

And those two are not possible without Yoga (10).”

Comments on ’Psychophysics’

Sri Aurobindo strongly disapproved the modelling of psychology on the line of physical sciences as early as 1916, when he began serialising `The Psychology of Social Development’ (later published under the title, The Human Cycle). In his essay on Materialism that appeared in 1918, he pointed out that:

“Only a limited range of the phenomena of life and mind could be satisfied by a purely bio-physical, psycho-physical or bio-psychical explanation, and even if more could be dealt with by these data, still they would only have been accounted for on one side of their mystery, the lower end. Life and Mind, like the Vedic Agni, have their two extremities hidden in a secrecy, and we should by this way only have hold of the tail-end: the head would still be mystic and secret. To know more we must have studied not only the actual or possible action of body and matter on mind and life, but explored all the possible action of mind too on life and body; that opens undreamed vistas. And there is always the vast field of the action of mind in itself and on itself, which needs for its elucidation another, a mental, a psychic science (11).”

At a time when behaviourism was in its hey-day, Sri Aurobindo had quipped (sometime between 1940-42),”….sense and reflex action becomes absurd if we try to explain by it thought and will (12).” He had remarked in 1925, “The difficulty is that they want to work in psychology in the same way that they work in physics. But psychology is not so simple. You can’t generalise in it as you can with matter. It is very subtle, and one has to take into account many factors (13).”

Comments on Psychophysiology

Sri Aurobindo had been commenting on the skewed views resulting from the mixing of psychology and physiology since 1916. In The Synthesis of Yoga (serialised between 1914-21), he pointed out that a psychophysiological perspective that considers the biological and physiological factors of our nature as the sole foundation of psychology could explain only, ”... the animal side of human nature and of the human mind in so far as it is limited and conditioned by the physical part of our being (14).” This would not suffice to explain human nature because the animal mind cannot even for a moment delink itself from its origins and become great, free, noble, magnificent, something which the mind in man can do as it can escape from ”the restrictions of the vital and physical formula of being (15).”

In the late 1940s, Sri Aurobindo gave a classic statement on psychophysiology (which he referred to as mixing of psychology and physiology), describing it as an “extended physiological”, not a “true psychological knowledge (16).” He explained that whatever psychophysiology revealed was not unexpected since we are a consciousness embodied and not disincarnate, acting through a body and therefore conditioned by the body. “The truth of things can only be perceived when one gets to what may be called summarily the spiritual vision of things and even there completely only when there is not only vision but direct experience in the very substance of one’s own being and all being (17).” He advocated that not psycho-physiological knowledge per se but “a psycho-physical knowledge with a spiritual foundation (18)”, would be more meaningful to understand human nature.

Comments on Altered States of Consciousness

Altered states of consciousness have become important sources for research in transpersonal psychology and in body-mind interactions. As early as in 1915, Sri Aurobindo had written:

“Modern psychological experiment and observation have proceeded on two different lines which have not yet found their point of meeting. On the one hand, psychology has taken for its starting-point the discoveries and fundamental thesis of the physical sciences and has worked as a continuation of physiology(19).” “The other line of psychological investigation is still frowned upon by orthodox science, but it thrives and yields its results in spite of the anathema of the doctors. It leads us into by-paths of psychical research, hypnotism, mesmerism, occultism and all sorts of strange psychological gropings (20).” He then proceeded to describe that though we do not have here, ”…..the assured clearness and firmly grounded positivism of the physical method”, yet facts emerge pointing out to dimensions of personality behind our superficial waking mind like the ‘subliminal self’, which though inconscient to the superficial mind is nevertheless itself conscient of the superficial mind and endowed with surprising faculties ....(21).” What Sri Aurobindo hinted in 1915 finds echo in parapsychological research as well as in the non-traditional, experiential approach employed by transpersonal researchers since the 1960s.

Comments on Heredity

In his 1915 essaytitled 'Evolution', Sri Aurobindo had commented that heredity was only a material shadow of soul-reproduction, of the rebirth of Life and Mind into new forms (22), a statement that has to be understood in its mystical sense. This comment was not made to undermine the scientific foundation of heredity but to place heredity in its proper perspective in the matrix of consciousness. He was more forthright in The Life Divine:

“Heredity upon which Science builds its concept of life evolution, is certainly a power, a machinery for keeping a type of species in unchanged being: the demonstration that it is also an instrument for persistent and progressive variation is very questionable; its tendency is conservative rather than evolutionary, — it seems to accept with difficulty the new character that the Life-Force attempts to force upon it. All the facts show that a type can vary within its own specifications of nature, but there is nothing to show that it can go beyond it. It has not yet been really established that ape-kind developed into man; for it would rather seem that a type resembling the ape, but always characteristic of itself and not of ape-hood, developed within its own tendencies of nature and became what we know as man, the present human being... The progress of Nature from Matter to Life, from Life to Mind, may be conceded: but there is no proof yet that Matter developed into Life or Life-energy into Mind-energy; all that can be conceded is that Life has manifested in Matter, Mind in living Matter.... Animal species in coming into birth may begin with a like rudimentary embryonic or fundamental pattern for all, it may follow out up to a stage of certain similarities of development on some or all of its lines; there may too be species that are twy-natured, amphibious, intermediate between one type and another: but all this need not mean that the types developed one from another in an evolutionary series. Other forces than hereditary variation have been at work in bringing about the appearance of new characteristics; there are physical forces such as food, light-rays and others that we are only beginning to know, there are surely others which we do not yet know; there are at work invisible life-forces and obscure psychological forces. For these subtler powers have to be admitted even in the physical evolutionary theory to account for natural selection; if the occult or subconscious energy in some types answer to the need of the environment, in others remains unresponsive and unable to survive, this is clearly the sign of a varying life-energy and psychology, of a consciousness and a force other than the physical at work making for variation in Nature (23).” This indicates that a consciousness and force other than the hereditary principle is also at work contributing to variations, refinements and mutations in Nature.

Sri Aurobindo’s line of thinking has a bearing for the interest in cloning experiments and the human genome project, “Even if it be discovered hereafter that under certain chemical or other conditions Life makes its appearance, all that will be established by this coincidence is that in certain physical circumstances Life manifests, not that certain chemical conditions are constituents of Life, are its elements or are the evolutionary cause of a transformation of inanimate into animate Matter. Here as elsewhere each grade of being exists in itself and by itself, is manifested according to its own character by its own proper energy, and the gradations above or below it are not origins and resultant sequences but only degrees in the continuous scale of earth-nature (24).”

Now, when the sequencing of the human genome has been probed thoroughly, it has been found that genetics alone is not sufficient to explain life’s complexity. Even complex human diseases cannot be simplistically traced to one or few major genes. It seems that calling DNA the book of life is an exaggeration. Rather the DNA can be compared to a random collection of words from which a meaningful story of life may be assembled. It is being argued that a genetic deterministic paradigm must give way to a new, more complex regulatory paradigm.

Richard Strohman writes in The California Monthly (25):

“If the announcements from the HGP (Human Genome Project) tell us anything, they tell us we do not know how organisms make themselves.... While it does tell us much about our genome, it tells us little about who we are and how we got that way.... We thought the programme was in the genes, and then in the proteins encoded by genes. But knowing all the individual proteins will not reveal a programme... The programme location is the cell as a whole, and the cell, through signalling pathways, is connected to larger wholes and to the external world.....

The real question for all of us is: who chooses, and who decides the future of life?”

Sri Aurobindo answered this existential question:

“If it be asked, how then did all these various gradations and types of being come into existence, it can be answered that, fundamentally, they were manifested in Matter by the Consciousness-Force in it, by the power of the Real-Idea building its own significant forms and types for the indwelling Spirit’s cosmic existence: the practical or physical method might vary considerably in different grades or stages, although a basic similarity of line may be visible; the creative Power might use not one, but many processes or set many processes to act together (26).”

Comments on Psychological Theories

Sri Aurobindo was pragmatic enough to admit the inevitability of a multitude of psychological and developmental theories to exist simultaneously, unlike the domain of physical sciences. He commented that the data in psychology was so `….subjective, fluid, elusive” that they “do not subject themselves to exact instruments, can lend themselves to varying theories, do not afford proofs easily verifiable by all (27) “He also wrote that, “….indeed, several conflicting theories hold the field together (28).” Sri Aurobindo also explained that to understand metaphysics either through psychology or through science was difficult: in the first case, psychological theories were like shifting quicksand on which no firm metaphysical building could be erected; in the second case, the whole basis of metaphysics tumbled every time science altered its views.

Yet, Sri Aurobindo viewed that metaphysical reasoning must be supplemented by psycho-logical insights to know the riddle of existence. Without psychology, metaphysics by itself cannot explain the world.

“All questions of the reality or unreality of the world, its fundamental or ultimate purpose or want of purpose, the destiny of the soul, must be left over till the psychological data have been understood.... Metaphysical reasoning by itself could only give us philosophical opinions, psychological verification makes.... truth a firm guide in life. It gives us a tangible ladder of ascension by which we rise to our highest truth of being (29).”

The Dilemma of Psychologists

Modern Western psychology started with an identity crisis. The perennial psychological flow throughout the ages had always acknowledged that psychology was the study of the soul or the Spirit, a view which was still reflected in the definition of psychology by The New Princeton Review of 1888. The early votaries of modern psychology had the dilemma of separating metaphysics from psychology and found their idol in Gustav Fechner, who applied quantitative measurements to the mind. Wilhelm Wundt had expressed his gratitude to Fechner for making psychology scientific. In an interesting overview, Ken Wilber showed that some of the leading psychologists, whom modern psychology eulogises as pioneers of scientific psychology and to whom are traced the credit of separating psychology from metaphysics, were either deep believers of spirituality or had carried seed-ideas obtained through intuitive lineage. Thus, Gustav Fechner himself had written a philosophical treatise where he explained that when one dies to the separate self, one awakens to the expansiveness of the Universal Spirit. Likewise, von Hartmann who wrote on the ‘Unconscious’ three decades before Freud was influenced by Schopenhauer, who in turn was influenced by the Upaniṣads. Freud, it seems, took the concept of the id from “Georg Groddeck’s, The Book of the It, which in turn was based on the cosmic Tao or organic universal spirit (30).” The dilemma is not only in the separation of metaphysics from psychology, but also in accepting that the some of the pioneers of ‘scientific’ psychology had spiritual connections in some way or the other.

This dilemma is not surprising as Sri Aurobindo has explained how after every banishment, the Divine returns with greater repercussions. Indeed, after its rejection by psychology, the Divine returned, albeit in a refreshingly new denouement in the transpersonal movement in psychology, at a time when the counter-culture movement was in its heyday. For historical reasons, the Buddhist influence in psychotherapy grew in stature as this was in consonance with the corresponding transition from the empiricism of modernism to the deconstruction of post-modernism. But after the deconstruction by post-modernism threatened to flatten or erase every unique identity, the Time Spirit necessitated a shift beyond post-modernism.

The post-post-modernism phase that followed post-modernism is conducive to a further progressive and dynamic spirituality. It is here that Sri Aurobindo’s transformative trajectory of the cosmic evolution gains significance as in his cosmology. The highest spiritual consummation does not blot out the individual uniqueness and identity. Instead, the individual becomes really unique by integrating oneself around a fourth-dimensional, ego-surpassing principle. This unique and integrated individual is then ready to traverse supra-cognitive or trans-cognitive fields so as to facilitate the manifestation of evolved human beings, almost with the stature of a new species in terms of consciousness. Such evolved individuals can form gnostic collectives which would mark a new denominator in social psychology too.

In this journey, the gains of modern ‘scientific’ psychology are not rejected but are appraised from a higher poise so as to serve the growth in consciousness. Sri Aurobindo correctly previsioned that a new and greater psychology was beckoning. For adherents of most of the creedal religions, psychology would at its best be a servitor of morality so that the individual, released from an imperfect existence could get succour in some heavenly afterlife. For believers in the Void, psychology would only serve to merge the individual identity with the cosmic consciousness or an undifferentiated Nihil. For votaries of Advaitism, psychology would merely serve to the point where the individual merges with the Transcendence.

Psychology would have little relevance if, at the end of life’s journey, the individual existence proved to be illusory. Only in Sri Aurobindo’s cosmology, the individual does not merge with the Cosmic consciousness or the Transcendence, but retains the personal uniqueness even when identified with the Transcendence or Cosmic consciousness. Psychology finds here its consummation in transformational spirituality. The trans-formation is effectuated through an evolution in consciousness. This implies that the present human being is a transitional being and is thus destined for a continual progress and dynamic change. Of course, modern psychology also serves a changing human being, but the change is assessed in terms of social changes, cultural transitions, ecological variables, genetic mutations and technological advances. But in Sri Aurobindo’s cosmology, the change is primarily an evolutionary change as the individual traverses progressively higher supra-rational cognitive matrices. Moreover, the evolutionary progression to manifest the highest Supramental Consciousness is bound to initiate corporeal changes so that the human body itself is destined to undergo a radical change. A new and innovative Consciousness-based Psychology arising from the Integral Yoga and vision of Sri Aurobindo cannot also be static, it has to progressively change to adapt itself to the shifting nuances of the evolving being and thus facilitate a new gateway to spirituality.

References

1. Sri Aurobindo. The Complete Works of Sri Aurobindo, Volume 12. Pondicherry: Sri Aurobindo Ashram Trust, 1997, pp. 315-16.

2. Ibid., p. 316.

3. Sri Aurobindo Complete Works, Volume 13; 1998, pp. 177-78.

4. Sri Aurobindo. Complete Works, Volume 21-22; 2005, p. 439.

5. Ibid., p. 24.

6. Sri Aurobindo. Complete Works, Volume 31; 2014, pp. 612-16.

7. (Recorded by) Purani AB. Evening Talks with Sri Aurobindo. 2nd Impression. Pondicherry: Sri Aurobindo Ashram Trust; 1995, p. 408.

8. Sri Aurobindo. Complete Works, Volume 35; 2011, p. 514.

9. (Recorded by) Purani AB. Evening Talks, p.611.

10. Ibid.

11. Sri Aurobindo. Complete Works, Volume 13, p. 194.

12. Sri Aurobindo. Complete Works, Volume 12, p. 275.

13. (Recorded by) Purani AB. Evening Talks, p. 408.

14. Sri Aurobindo. Complete Works, Volume 23-24; 1999, p. 624.

15. Ibid.

16. Sri Aurobindo Complete Works, Volume 12, p. 319.

17. Ibid., p. 320.

18. Sri Aurobindo. Complete Works, Volume 23-24, p. 624.

19. Sri Aurobindo Complete Works, Volume 13, p. 178.

20. Ibid., p. 180.

21. Ibid.

22. Ibid., p. 174.

23. Sri Aurobindo. Complete Works, Volume 21-22, pp. 861-63.

24. Ibid., p. 861.

25. Strohman R. The California Monthly April, 2001.

26. Sri Aurobindo. Complete Works, Volume 21-22, p. 862.

27. Sri Aurobindo Complete Works, Volume 12, p. 318.

28. Sri Aurobindo. Complete Works, Volume 21-22, pp. 860-61.

29. Sri Aurobindo Complete Works, Volume 12, p. 313.

30. Wilber, K. Collected Works, Volume 4. Boston: Shambala; 1999, pp 426-27.

Dr. Soumitra Basu, a practising psychiatrist and member of SAIIIHR, is the Director of a school of psychology, Integral Yoga Psychology. He is also one of the editors of NAMAH.

Share with us (Comments,contributions,opinions)

When reproducing this feature, please credit NAMAH,and give the byline. Please send us cuttings.